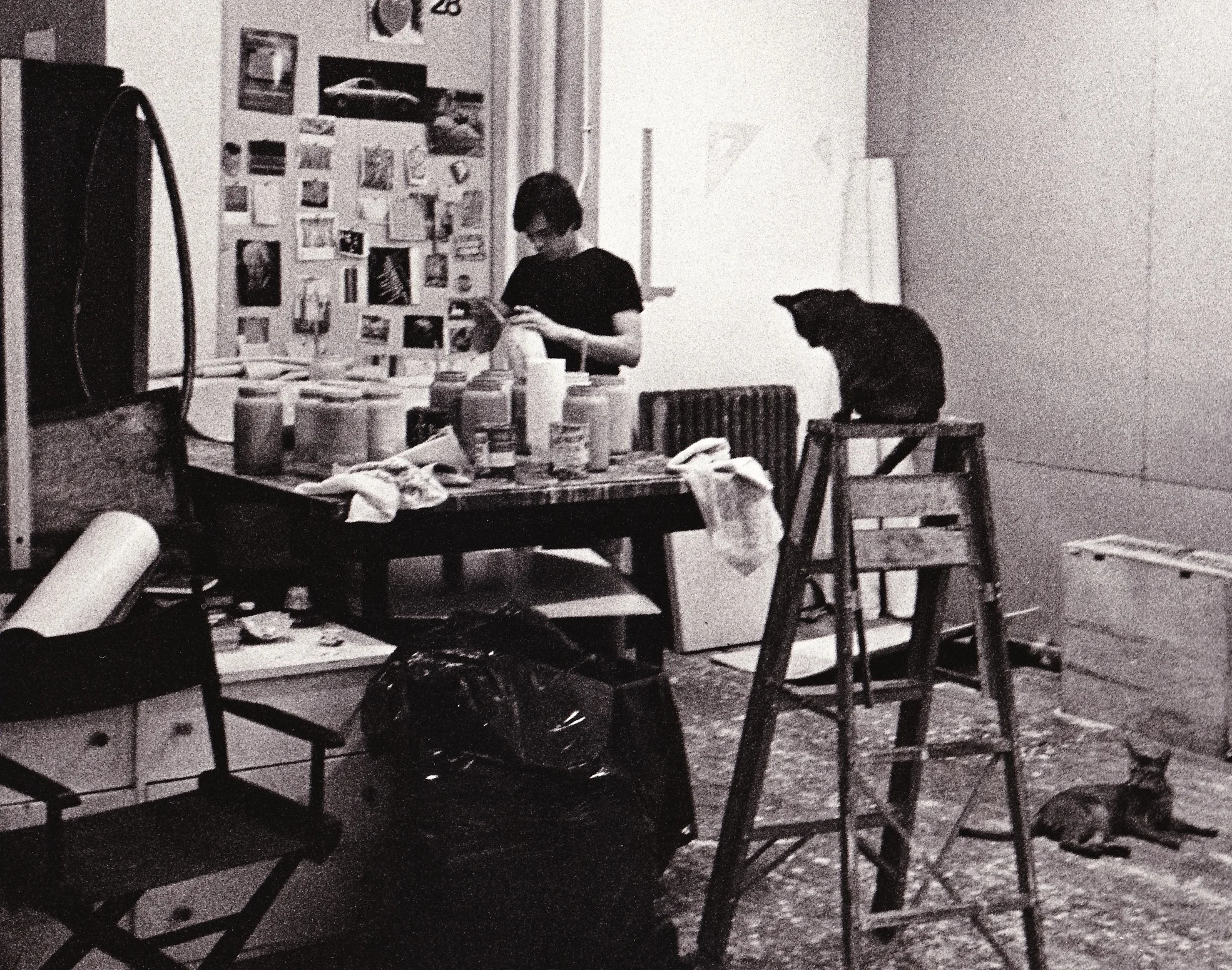

William Ridenhour began Painting professionally in New York City in 1964 after completing a University education in Science, Philosophy, and Literature. For the next three years he was painting in a small studio apartment and working various odd jobs, primarily in publishing. In 1967 he rented his first Studio and produced a series of large scale Paintings.

Although he had no formal education as a Painter, his work and reputation soon attracted the interest of a number of Artists of the New York School. Robert Motherwell, Jasper Johns, and Ellsworth Kelly were some of his earliest supporters. Helen Frankenthaler, Elaine and Willem De Kooning also became advocates of his work. Long personal/professional friendships including intellectual conversations concerning Art and Philosophy with these stalwarts influenced and encouraged the development of his own unique Painterly Ideals without the limits of one particular style.

In the winter of 1969 Robert Elkon of the Robert Elkon Gallery (then located at 1063 Madison Avenue) invited Ridenhour to exhibit two large canvasses in a spring Group Show. Subsequently, he showed new work at the Elkon Gallery in Group Shows through 1971 and was commissioned in 1972 for his first one man show. Elkon became the primary Dealer of Ridenhour Paintings featuring his work constantly in Individual shows and Group shows for the next eleven years. The Painter was challenged by the Dealer to provide something New, in style and scope at each viewing. This aggressive symbiotic friendship produced some of Ridenhour's most diverse yet interestingly, identifiable Works of his early career. Reviews in The New York Times, Art News, Art in America and other newspapers and periodicals were very positive. At his 1982 Solo show the Art critic/historian Linda Cathcart called Ridenhour "the most important young Painter of his generation"! While planning another Solo show exhibiting exciting new Paintings and a retrospective of earlier work in order to showcase his depth, range and vision Mr Elkon became ill and died. Ridenhour was devastated, and the ensuing scramble by other Dealers and the stark hustle of the business side of being an Internationally known Painter was the beginning of his disillusionment with the New York Art scene.

Listed below are recently researched reviews and magazine articles. The narrative will continue next month.

Article by Hilton Kramer Published March 20, 1981

William Ridenhour (Elkon, 1063 Madison Avenue at 80th street): The paintings of William Ridenhour are filled with arresting images. A floating grand piano shares pictorial space with a photocopying machine in one untitled work, for example; and in another, called "Clear Light," a huge blowup of a black beetle is shown beside a red snapper. Elsewhere there are double figures sharing space with their reflected mirror images, and meterological maps of North America of the sort we see on television weather forecasts. Yet while these and other images arrest our attention, what sustains it is the forceful way Mr. Ridenhour paints. Using high saturations of color in a vigorous painterly manner, yet anchoring everything in a "free" but clearly articulated style of drawing, he manages to keep all these unlikely images pictorially vivid. The smaller works on paper, especially the still life called "Snick-a-Snack," are especially fine. (Through Wednesday.)

Article By John Russell Published February 13, 1987

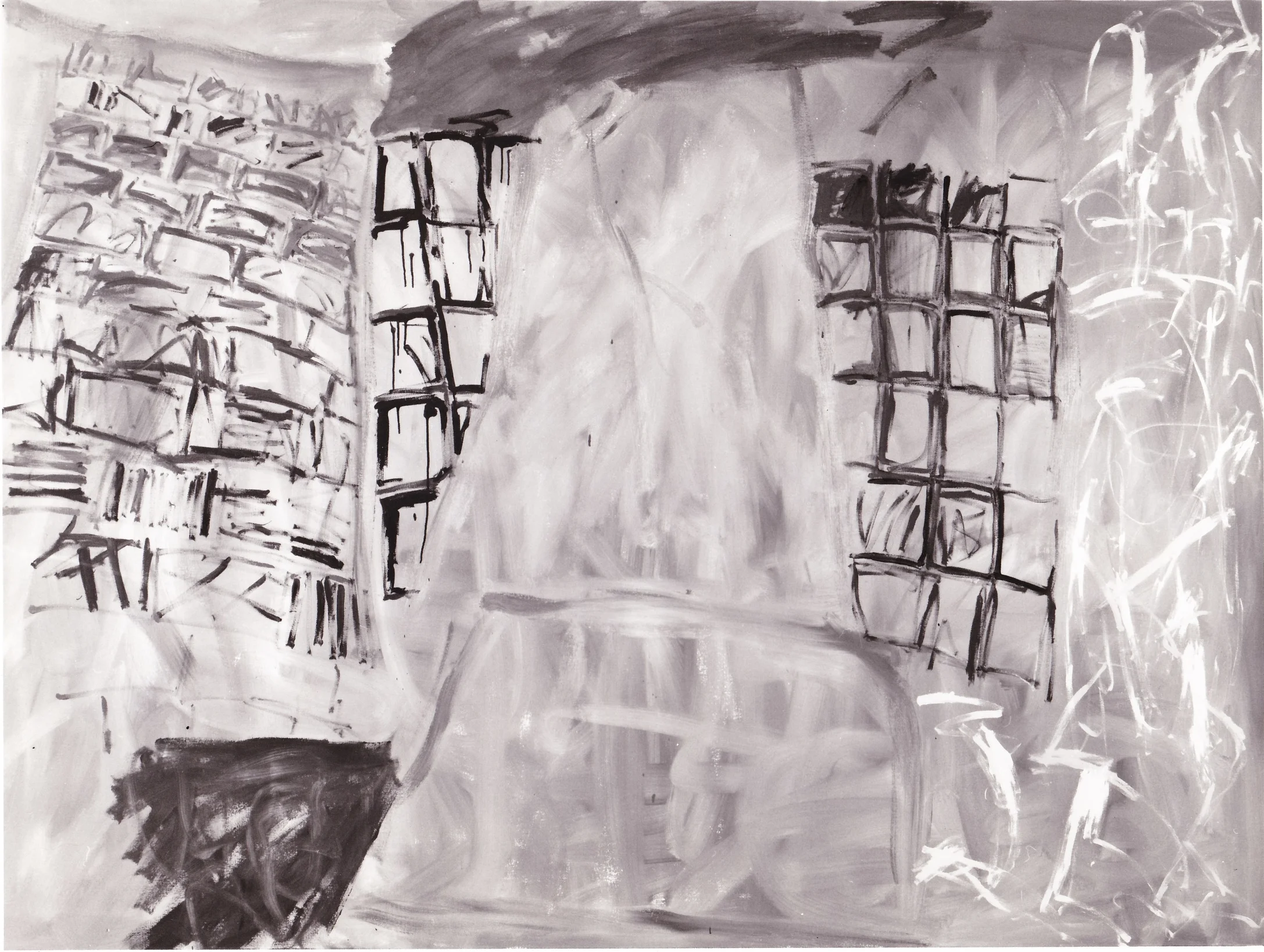

William Ridenhour is another painter of whom it would be good to see more. His two paintings of Marsden Hartley's studio (a former church) have a curious, light-filled echo to them, as if the spirit of Mr. Hartley were still around, filling the two-storied interior with emanations that set it apart. (Even the sky cooperates.) Mr. Ridenhour has also a vein of personal fantasy that is all the more intriguing for being rendered in a matter-of-fact way. There is nothing matter-of-fact about a situation in which a red snapper is kept under surveillance by a water beetle the size of a bull terrier, but the grave, unhurried application of the paint dares us to think it out of the ordinary. As for the red-gold pheasant that is caught in the act of falling out of a yellow armchair, it is difficult to say whether common sense or gravity is the more affronted by it. Either way, this is a tantalizing group of images.

By Thomas Hess Published December 4, 1972:

William David Ridenhour, a talented young painter, has a strong first one-man show at the Elkon gallery (1063 Madison Avenue at 81st Street, through 11/30). Simply arranged stripes - like book-spines in a bookcase - in gleaming irridescent colors, are fitted into simple rectangular units. Snow-whie paper shines through - Cezanne and buttefly-wings.

Article by Vivien Raynor Published January 18, 1980

William Ridenhour (Elkon, 1063 Madison Avenue at 80 Street): William Ridenhour's work has changed so much since his show of last year that this observer failed to recognize it. Before, he specialized in a labored kind of primitivism that combined abstraction and representation and sometimes invovled a crudely colored image that resembled a brick wall. Now, especially when working on paper, he begins by distributing washes in spectrum colors on a white ground, then mottles them with dabs of impasto in the same colors. Gradually, the treatment discloses still lifes or interiors, such as one featuring orange twin beds. This, at the same time, is an all-over design of dots and washes in which the central orange gives way to yellow, green and blue and, at the rim, magenta and olive. The technique is not, though, the artist's final word: he presents two compositions - on white and black respectively - involving a precisely painted red-and-blue fish with a purple iris, and another black canvas containing two red peppers and two gray airplanes. Taking still another approach, the artist pays homage - inadvertently perhaps - to Lee Krasner by covering a canvas with black eye forms, on which he imposes brilliantly colored birds. Planes, peppers, bananas and sliced grapefruit recur idiosyncratically is the pictures, giving them all jocular tone. But, in general, Mr. Ridenhour seems to be headed in a more interesting direction than before, one that could take him into the mythic territory inhabited by the late Jan Müller. (Through Feb. 7.)

"Knowing What I Like", Kouros Gallery, New York, 1987 Curated by John Bernard Meyers

William Ridenhour - Often in medieval illuminations and Byzantine icons, we are amused by the placement of the hierarchies - from the Lord to angels to kings to common folk. But are these depictions simply a question of who is more important and who less? Perhaps it was an aesthetic attempt to solve the mysteries of space - to give depth to a flat plane before the convention of perspective. The Cubists and the Abstract Expressionists questioned the Here, and what is over There with still other approaches. In the 18th century, the philosophers of the Enlightenment much admired wit: the ingenuity demonstrated by unexpected combinations of ideas or expressions. The artist thus gifted often wittingly knows what he is doing - this our delight in the witticisms of Klee, Miro, and Picasso.

The paintings of Bill Ridenhour would please Diderot because the Here and There is made clear through the curve of the artist's field of vision. Displacements occur which are unnatural: a water beetle is many times larger than a red snapper swimming far below; neither live in real water but in a wonderful light spume of swirling pigment. A pheasant in front of a large yellow arm chair is falling to the floor; it is up to us to decide, if we must, how he got there and where he's going. As we look at Marsden Hartley's studio church, it slowly drifts away from being a sturdy New England dwelling to a cardboard-like, untethered structure which barely hold on to its Islamic-domed tower. The Cork Orchard seems to grow backward, but its sky, menacing to both viewer and cork trees, threatens the foreground.

William Ridenhour B. 1941. Roanoke, Virginia

Shoe In 1979 Acrylic on Canvas - An egg carton, banana peels, diving bird, soaring plane, and trunk roar across WIlliam Ridenhour's painting as though he has lung them from the studio floor onto te work's flat surface. But what is the focus of this mesmerizing chaos? Ridenhour's blue shoe, with its heel pointing up toward the left-hand corner, literally is "in" the canvas, serving as a visual pun on the title.

Ridenhour's vivid colors add an urgent intensity to his centrifugal composition. The hues reflect an interest in bright colors that he shared with other New York City artists working in the 1960s and 1970s. But Ridenhour uses neither his palate not the specific images themselves to limit his tale to a specific incident, but instead "wants each person to make up their own story."

"652 Broadway" Article by David Shapiro Published June 1971

Two artists, William T. Williams and William Ridenhour, work in the same loft building, both paint abstractions, but otherwise fly off in opposite directions; Williams recently exhibited at Reese Pailey; Ridenhour will show at Elkon

William Ridenhour is on the fourth floor; here one experiences the freedom of streaming. He paints a scatter of simulated water measured against the so-called grid, which sharpens the confine. His principle of streaming employs empty spaces and strewn decoration somewhat like the ancient discontinuous mosaics of Trimalchio spilling the wine. Yet Ridenhour's articulations have never been clearer, with less emphasis on the contingent, and with the inclination of flow in the ultimately balanced or equitably distributed diagonals. Giotto too with his "considerable experience" adopted the gridiron. in the new works one must look very carefully before you find the grid. Life itself is scattered, and Roman pavements are but beautiful proof. Scattering over a fairly cunning, fairly concealed metrical arrangement is an inheritance, as Meyer Schapiro has reminded us, as much as the silhouette or the central figure. in Ridenhour's streamed works, Eros stands lightly on the ledge: a sensuality that returns us to the Greek inscription, "Hello, good and happy one." The structure is antithetic, however, to the unintelligible lyricism of the last decade. There is the tensed ground. Above it, in freedom, the steam, heavy but beautiful. Behind it, leaning slightly on the the painter's hand, tradition. Our glance, directed by the grid but lightly, is the final effort. In time, all the edges oscillate and the values themselves have a variable, with a rather free flickering of the dark. Nevertheless, not a road map. The color is there defining and giving limits and making limitless; for example, a yellow stream is moving but underneath it there are two yellow blocks that are definitely not going anywhere. Visually they may be stepped up from one to another, life an excited electron, but there is always the definite diagonal, the internal logic, a premeditated simplicity of attack.

The colors are not forced or toned - here the most obvious difference from Darby Bannard's pieces, which have otherwise influenced Ridenhour - or keyed to a particular value to hold them on to the picture plane, but held by relationship, placement. The interest in surface is also complex - there is an alliance with texture (say of stained mulberry paper) but not with attack. His work does not have the central, highly glossed rectangles of Bannard, nor the sharp object sticking up. The plastic paints thicken and there is unavoidable gloss but there is also concern for the subtle sandpaper texture and light wheat color of bare canvas. Reinforcing a belief that the great tradition of American painting is writ in water and line (Pollack and Johns), he has created an abstraction in which watercolor marries drawing. There is a federation of the mathematical grid and expressive superimpositions; the unpainted rectangles paradoxically become the literal ground and yet jut out as the most prominent portion of the painting, with most of the canvases having counter-diagonals based on color relationships. These create a certain balance and an implied balance, an obvious but not always true balance, and Ridenhour comes close to being, like Kelly, a "genius of the obvious." The grids are reminiscent of an experiment the artist once did for the Atomic Energy Commission of counting the yeast cells over a slide calibrated in a grid pattern. One does not like the idea of the amorphous; one is interested in clarity, rationalism and (delayed) gratification. Reinhardt, for example, is not an exhaustible experiment. The problem is not how large an idea will work, but how much largeness one can have within a small-scale painting: not meticulousness or monumentality.

Ridenhour has worked for the Navy upon the physiology of shells (one need not apply biological methods to his own ornamentation), with oysters particularly, because they produce that ersatz shell slowly, looking at the crystalline structure. The paintings themselves are preoccupied with such a dissolved or dissolving structure, and the process of structure as it builds up. ("I always thought of Noland's targets as X-ray diffraction patterns - a perhaps irrelevant association but it didn't diminish them.")

He decides first on the particular format - spends several days making color choices - then mapping out the ground rectangles - and moving on the superimpositions which are indeed not X-ray diffraction patterns or blowups of yeast cells but are as strange: as when one has left a certain tissue under the microscope and upon returning it is something else; it has dried up - and become what Ridenhour calls "tortured pattern." One thinks of the painter as a child, fascinated by microscopes and telescopes, one eye on the cell, the other on the dirigible hanging in the middle of the highway. He has been attracted to the idea of painting without a ground, but is not attracted to the surface of glass. One of the primary reasons he is involved with primary colors and grids is that he likes the metrical arrangement of colors into norms, balancing the so-called "natural" and "unnatural", giving to each of the rectangles its particular echo, one way of handling the by now comical Problem of the Edge is to repeat the edge internally; the picture may appear to stream off the edge, but at the same time there is an echo, a microcosm, a frame of reference, a record through paradigm of what is going on within the whole. He has echoed all the corners; a corner abutting here or there echoes the corners of the painting as a whole, an internal record of echoed corners. Born in Virginia, he says, "Virginia itself is painting, particularly the western part, Roanoke, surrounded by an almost perfect ring of mountains with a mountain in the center." Color echoes this heritage and is not dramatically separated form the repetitions of form (at one point he played around with calling a group of pictures Catawba, because of the blue haze of the mountains when flecked by dramatic changes in October) - thus over a blue rectangle blue is applied but it spills in the red field and the red into the blue becoming a woven form, a fugue, a subject piling up on itself.

He is now painting in logical fragments within a more monochromatic field, on mulberry paper, and assembling with a darker preoccupation with a seemingly frangible surface, not literally but figuratively, "tearing up." Funkiness being doomed and throwaway sculpture being a throwaway idea and the earth-workers coming by their failure of nerve legitimately... Psychoanalysis has not affected him at all, except to give him the courage to work. One dream that does leave the same physical impressions as his paintings for me is a subterranean experience, with panic at the bottom and a striving for the surface, going back down and coming up through layered depths (Hokusai).

These are luxurious paintings - something he can do - with the high unity of floral or abundant Lichtenstein, a look achieved with a minimum of means. The composition is rigorous, the line incredibly rigorous. In the last works, the line and process of making the line do not seem to come by the principle of the easiest way, but finally this is the line that he doesn't arrive at except by resolution and concentration of wash, like a stenciled sea-piece. He is not ennucleating or containing the kitchen-sink, nor is he interested in things as stepping stones. He has worked with anemones, but "not as flowers." In his youth, airplanes would fly over and his father would say, "Identify." His painting (as when G. Stein looked from a plane and all was Masson underneath her) has an aerial view and is not a child of peace but of a prevalent sensuous paranoia.

The merely lyric, the uselessly scalloped, the Hofmannesque, as for example in Bannard, is valid, but it is not his approach. Ridenhour's work of his generation seems most intelligent and ergo most intelligible. He has spent most of his time peering through optical devices and has painted constantly, never drawing people or things, through in geometry he liked to make A and B represent a lighthouse. Like the propositions of classical geometry, his painting will not give rise to controversy nor does it need that support.

Article by David Shapiro

William David Ridenhour (Elkon, May 3 - 29) - William Ridenhour's second one-man show was a dramatic discontinuity from his previous work and included 17 ink paintings and an ambitious Triptych. Ridenhour prepared for his work by acquainting himself with canonic Chinese techniques under two Chinese masters of "bird and flower" and landscape themes. He has maintained a Chinese economy with an expressionist bias in these new pieces. Using a Chinese brush and paper towels on Arches paper with a scale of 62" length and 28-36" in width, he intended to emulate the Chinese master of color modulation within monochrome. Gouache and acrylic superimpositions act dynamically over the darker systems, moreover, as a sudden blue passage in "Undertow" or a series of pink droplets in "David Combs." Rendered quickly, in a matter of 15 seconds, they do not have that look and remind one of Moliere's "Time is irrelevant," except that the work is involved with duration.

These contemplative works, exploratory and felt but not lazy, require intimate duration and cannot be absorbed at first glance. They are watery paintings of flux, from which a figure may emerge as a species of comment on deKooning, as in "Wrought." The black tones may seem menacing or introspective, but this is not introspection writ large, but an enticement, full of the lavish heights and depths of Chinese scapes, an expansive economics. Unlike Serra, they are also drawings that disdain to be concerned with strength and strength alone.

An element of sculpture does emerge, nevertheless, when the paintings at best seem moulded out of a block of black ink. Ink is the common experience in all the pictures, but is fluidity seems as changeable as the eye. Ridenhour escapes the familiar problems of the edge by framing all of these sculptural "portraits" by one or two inch white boundaries that modestly remind one of what they are, disciplined discernments on paper.

Monochromatic can be a blindness where the world is reduced to greys, but here, for example, in "Streams and Mountains Far from the World" we are reading a work dignified by dynamics in color as much as in its structural syntax. Anti-reductivist, this work admits to being born an abstract expressionist, among other things, and making do quite richly with this influence. About this influence its is not melancholy or malicious and while its primary concerns are not "heroic" it does not dwindle into the merely decorative but reminds us of the values of intense decoration in complex and unified compositions. Though this show was conceived as one painterly episode, no discards, no editing, at high calligraphic speeds, the pieces stand far from mere facility. The remind us that painting was and can be a form of private devotion and they emit their life slowly and with charm.

"Critics' Choices, Art" Article by Hilton Kramer Published October 4, 1981

Small galleries specializing in "big" art - big in names, in quality and in promise for the future, if not always in the physical dimensions of the objects shown - used to be one of the most delightful features of the New York art scene. Over the years they have been largely superceded by the the big galleries that specialize in small art (which is often very large indeed in its physical dimensions). One fine gallery that has not significantly changed either in its scale of operation or in its dedication to quality, however, is Robert Elkon's, which is currently observing its 20th anniversary. To mark this event, the gallery has mounted an exhibition that brings together a representative selection of the modern master works and the art of contemporary painters and sculptors for which it has become renowned.

Called "Two Decades," the show ranges from the most celebrated names - Picasso, Matisse, Magritte, Dubuffet, Giacometti, Kandinsky, et. al. - to those of artists of very recent reputation. The art of the New York School - Pollack, Motherwell, Kline, Baziotes and Still - shares attention with that of the School of Paris. The painters of the Color-field school - Morris Louis, Friedl Dzubus and Jack Bush - are included, and so are Jean Arp, Auguste Herbin and other European eminences.

Yet this anniversary exhibition is not entirely historical in its outlook. Recent works by William Ridenhour, Jean-Pierre Pericaud and John Walker, among others, are also part of the survery, this giving us a fully rounded account of the scope of the gallery's artistic interest. The show will stir some happy memories for those who have been around long enough to have followed the gallery's progress, and will introduce newcomers to some splendid works of art. It remains on view at 1063 Madison Avenue (at 80th street) through Nov. 4.

Article by Ruth Bass Published September 1981

William Ridenhour (Robert Elkon): Bright color and jazzy brushwork enliven odd, often inexplicable images in Ridenhour's recent acrylics. A weather map complete with cloud pattern may provide the occasion for garish, messy brushwork, or a wallpaper pattern may vibrate against hidden or reflected images, momentarily seeming to become real foliage and trees. Often the tension is provided by the incongruous placement of three-dimensional objects in what is essentially a two-dimensional context.

In Caracara, for instance, the bottom of a volumetric fuchsia armchair thrusts down from the upper left, while the right side of the painting is occupied by the head and shoulders of a southern hawk almost squeezed between a pastiche of broad white strokes and the light, bright green background. Even more striking is the image of a huge black beetle that seems to be attacking a red fish. The fish, in its haste to escape, leaves a white wake in the pale blue field - a field that looks more like sky than water. In some works, however, the images go out of control - too kitschy, arcane or wildly painted to be real.

Article by John Yau Published September 1981

William Ridenhour at Robert Elkon - The best painting in WIlliam Ridenhour's recent show of eight acrylics and three watercolors was Clear Light. On a thinly applied pale blue acrylic background, two images appear: the smaller, a reddish-orange carp; the larger, a blackish beetle. The carp shoots up diagonally from the lower left-hand corner and is intercepted by the beetle. Short, thin strokes of color emphasize te carp's scales, fin and spine, longer curving strokes convery the beerle's armor-like plating, while branch-like calligraphic marks translate into its legs. Each stroke and wash of color has an air of rightness and necessity.

The visual juxtaposition of the two creatures is bold and surprising. Why and how they have collided is a question neither quickly dismissed nor easily answered. I see their conjunction as related to Surrealism's emphasis on the startling juxtaposition. This connection to Surrealism makes Ridenhour substantially different from many of the painters currently exploring the ground between abstraction and representation. He is neither emblematic, like Susan Rothenberg and Lois Lane, nor ieratically juvenile, like Louisa Chase. Rather, he explores the possibilities of Surrealism without succumbing to its tendency toward excess - he restricts himself to a few images, usually two or three. In most cases his paintings do not seem literary, iconic or anecdotal. Nor does he resort to Surrealist techniques like automatism, anatomical distortion or dril academic illusionism. By juxtaposing two or more images, he suggests a relationship that invites the viewer to supply the narrative. Yet in his best paintings the narrative remains elusive.

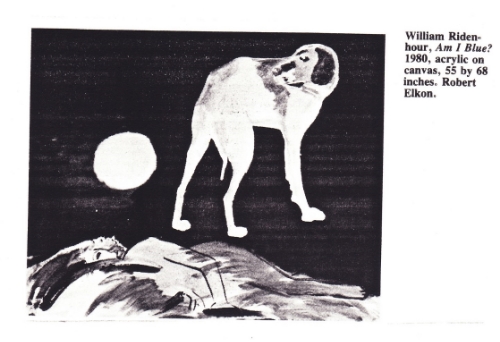

In Ridenhour's erotic paintings, on the other hand - Mission II, Sextet and Am I Blue, all of which contain the outline of a nude - the Surrealist connection sometimes considerably mars the work. In Mission II, there are, in addition to the nude, two bananas and a camera; it is not difficult to supply a narrative, nor is it particularly interesting. The voyeuristic overtones weaken the painting's impact, suggesting that Ridenhour should avoid cynical whimsy.

In I Am Blue a sleeping woman's figure lies along the bottom edge of the canvas, her outline forming a landscape. Hovering above her, on a dark blue ground, a dog looks over its shoulder at the moon. None of these images touches another; their isolation suggests Rideour's own isolation from he traditions of both abstraction and representation. Rather, and again, like the Surrealists, RIdenhour seems to derive his images from that myth-making territory known as the artist's psyche. His best paintings remind me of the Surrealist poet Robert Desnos's saying, "Poetry may be this or it may be that. But it shouldn't necessarily be this or that ... except delirious and lucid."

William Ridenhour

Solo Exhibitions

Robert Elkon Gallery, New York, 1972, 1975, 1978, 1980, 1982

Group Exhibitions

"Jazz and Girls". Galerie Craven, Paris 1973

Annual Group Exhibition, Robert Elkon Gallery, New York, 1972-1983

Harkus Krakov Gallery, Boston, 1975

Sunne Savage Gallery, Boston, 1978

"Painting and Sculpture Today", The Indianapolis Museum, Indiana, 1978

"American Painting: the Eighties" Grey Art Gallery, New York, 1978

curated by Barbara Rose

"The New American Painting", Janie C. Lee Gallery, Houston, 1979

"Knowing What I Like", Kouros Gallery, New York, 1987

curated by John Bernard Myers

"Abstract Paintings: The 90's", Andre Emmerich Gallery, New York, 1992

curated by Barbara Rose

Important Collections

Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Newark Museum, Newark

Rose Art Gallery, Brandeis University

Chase Manhattan Bank, New York

Owens Corning Fiberglass

Atlantic Richfield Corp., Dallas

Atlantic Richfield Corp., Los Angeles

Mr Richard Brown Baker, New York

Mr Albert List, New York

Mr N. Richard MIller, New York

Sir George Weidenfeld, London

Mr Graham Gund, Boston

Henry and Maria Peiwell, New York

Rapid American Corp., New York

Pacific Security National Bank, Los Angeles

Art Programs, San Francisco

AT&T Art Collection at The University of Texas at San Antonio

Bibliography

"652 Broadway", Art News, June 1971, Article by David Shapiro

New York Magazine, December 4, 1972, Review by Thomas B. Hess

New York Times, March 24, 1978, review by Vivien Raynor

New York Times, September 24, 1978, review by Hilton Kramer of "Art of the Eighties"

Village Voice, September 24, 1979, review by Carrie Rickey of "Art of the Eighties"

Art in America, October 1979, review by Roberta Smith of "Art of the Eighties"

New York Times, January 18, 1980, review by Vivien Raynor

Art in America, September 1981, review by John Yau

Art News, September, 1981, review by Ruth Bass

New York TImes, March 20, 1981, review by Hilton Kramer